Welcome home! Please contact lincoln@icrontic.com if you have any difficulty logging in or using the site. New registrations must be manually approved which may take several days. Can't log in? Try clearing your browser's cookies.

Pain and Suffering. Golden Dream or Red Herring?

Pain and Suffering. Golden Dream or Red Herring?

When dealing with the belief in an all-powerful and all-loving God, the existence of pain and suffering becomes extremely problematic, if not outright impossible to reconcile with the world around us.

Those who would address this issue, tend to either explore it inadequately, simply sidestep the issue altogether, or blatantly deny it.

Whether through experience (my faith crisis of '87), or through academic study, or plain and simply reason, this is one exceedingly difficult stumbling block to overcome.

Of course God doesn't need to figure in this equation. I only mention this because it was the starting point of my journey. This doesn't need to be an exclusively theistic problem. I've since moved away from approaching it from this angle. Pain and suffering are just as challenging to non-theistic beliefs as well. Unless we are willing to accept and convert to a bleak and soulless form of atheistic materialism. But be prepared to abandon any form of spirituality, beauty, love, art, music, etc... the list goes on. No, atheistic materialism isn't the answer either.

~

What if pain and suffering aren't the same thing? Is it possible to suffer without pain? Is it possible to feel pain without suffering? Suffering is not the same as pain, although most of us see them as synonymous. (Granted, it is not always easy to distinguish the two).

I have personally experienced pain without suffering on several occasions.

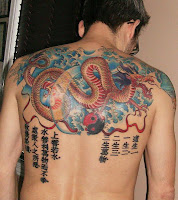

I have my entire back tattooed. It was a 25 hour ordeal.

It was painful. There was one point that I began uncontrollably shivering. My body was going into shock. But I would not use the word 'suffering' to describe this experience.

When I tested for my Black Belt in Taekwon-do, I could describe it as painful. It was a brutal three and a half hour experience that pushed me close to my physical and mental limits. (And incidentally, it was during this examination that I inadvertently stumbled across my first taste of mindfulness. I was previously aware of it, but being aware of it by definition and experiencing it are drastically different).

And finally there's childbirth. Although I have experienced childbirth twice, I cannot say I've experience the pain of it. However, my wife doesn't describe the experience as suffering. There was no suffering. Pain, yes. But suffering? No. I think it is because there is purpose and hope present. At some level I think we instinctively understand that these pains are normal and maybe even necessary.

Although I could continue on about experiences of suffering without pain, I'd rather stay away from that darkened avenue.

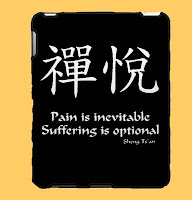

Pain is an unpleasant sensation.

Pain is an unpleasant sensation.

Suffering is a mental and emotional response.

Pain is an inescapable part of life as we know it; it is inevitable.

Suffering is optional.

It is the delusional belief that we deserve to live life pain-free that is the cause of much of our suffering.

Pain and suffering are so closely related in our minds - in our beliefs - that when pain arises we usually respond immediately with resistance. We respond with resistance because we believe pain shouldn't happen to us. That belief we cling to is a source of suffering. The greater we struggle with the undeniable presence of pain, the greater our suffering. It is that belief which causes us to become delusional as it is inconsistent with reality.

Alongside our delusional denial of pain is also our denial of death. Few people really give this dreadful topic much thought. We don't want to die: in fact a great many people I know build their entire belief-system or faith upon its denial.

I really like Lin Yutang's shocking biblical interpretation of God's intention for Man's immortality in his book, "The Importance of Living" (pg. 16)

In the various mindfulness traditions I think there's hope.

Suffering occurs when the mind responds negatively to the sensations it identifies as pain. The key to diminishing the suffering that we usually connect to physical pain is acceptance. Acceptance means confronting unwanted pain without hatred and especially without fear.fear. And this acceptance also means a willingness to abandon some of our beliefs. To allow room for a faithful doubt, rather than a doubtful faith.

The moment we attempt to make our beliefs fact is the moment suffering begins. It can only give birth to anger, fear, panic and disillusionment and strengthen the fetters that bind us.

I don't think there's anything wrong with having beliefs, so long as we acknowledge them for what they are and are not. (Simply beliefs, not facts).

It is when the Ego attaches itself to our beliefs that we wade into trouble.

When dealing with the belief in an all-powerful and all-loving God, the existence of pain and suffering becomes extremely problematic, if not outright impossible to reconcile with the world around us.

Those who would address this issue, tend to either explore it inadequately, simply sidestep the issue altogether, or blatantly deny it.

Whether through experience (my faith crisis of '87), or through academic study, or plain and simply reason, this is one exceedingly difficult stumbling block to overcome.

Of course God doesn't need to figure in this equation. I only mention this because it was the starting point of my journey. This doesn't need to be an exclusively theistic problem. I've since moved away from approaching it from this angle. Pain and suffering are just as challenging to non-theistic beliefs as well. Unless we are willing to accept and convert to a bleak and soulless form of atheistic materialism. But be prepared to abandon any form of spirituality, beauty, love, art, music, etc... the list goes on. No, atheistic materialism isn't the answer either.

~

What if pain and suffering aren't the same thing? Is it possible to suffer without pain? Is it possible to feel pain without suffering? Suffering is not the same as pain, although most of us see them as synonymous. (Granted, it is not always easy to distinguish the two).

I have personally experienced pain without suffering on several occasions.

I have my entire back tattooed. It was a 25 hour ordeal.

It was painful. There was one point that I began uncontrollably shivering. My body was going into shock. But I would not use the word 'suffering' to describe this experience.

When I tested for my Black Belt in Taekwon-do, I could describe it as painful. It was a brutal three and a half hour experience that pushed me close to my physical and mental limits. (And incidentally, it was during this examination that I inadvertently stumbled across my first taste of mindfulness. I was previously aware of it, but being aware of it by definition and experiencing it are drastically different).

And finally there's childbirth. Although I have experienced childbirth twice, I cannot say I've experience the pain of it. However, my wife doesn't describe the experience as suffering. There was no suffering. Pain, yes. But suffering? No. I think it is because there is purpose and hope present. At some level I think we instinctively understand that these pains are normal and maybe even necessary.

Although I could continue on about experiences of suffering without pain, I'd rather stay away from that darkened avenue.

Pain is an unpleasant sensation.

Pain is an unpleasant sensation.Suffering is a mental and emotional response.

Pain is an inescapable part of life as we know it; it is inevitable.

Suffering is optional.

It is the delusional belief that we deserve to live life pain-free that is the cause of much of our suffering.

Pain and suffering are so closely related in our minds - in our beliefs - that when pain arises we usually respond immediately with resistance. We respond with resistance because we believe pain shouldn't happen to us. That belief we cling to is a source of suffering. The greater we struggle with the undeniable presence of pain, the greater our suffering. It is that belief which causes us to become delusional as it is inconsistent with reality.

Alongside our delusional denial of pain is also our denial of death. Few people really give this dreadful topic much thought. We don't want to die: in fact a great many people I know build their entire belief-system or faith upon its denial.

I really like Lin Yutang's shocking biblical interpretation of God's intention for Man's immortality in his book, "The Importance of Living" (pg. 16)

"God did not want man to live forever. This Genesis story of the reason why Adam and Eve were driven out of Eden was not that they had tasted of the Tree of Knowledge, as it popularly conceived, but the fear lest they should disobey a second time and eat of the Tree of Life and live forever.""We were never meant to live forever and we never will. Doesn't chasing this golden dream (or red herring?) of immortality, whether it is some form of favoritism or an earned reward of Heaven for doing or saying the right things make us little more than spiritual hedonists? I'd like to believe humanity has the potential to grow and evolve these altruistic traits without being threatened into obedience or bought with rewards. I'm not saying that a spiritual life doesn't continue after physical death. It's that any position we hold is little more than conjecture - or projection - at best. Because we choose to believe it doesn't make it true. But it does affect how we live our lives.Our compassion becomes highly suspect and conditional and maybe even self-serving. Doesn't this contribute to the suffering of the world?

In the various mindfulness traditions I think there's hope.

Suffering occurs when the mind responds negatively to the sensations it identifies as pain. The key to diminishing the suffering that we usually connect to physical pain is acceptance. Acceptance means confronting unwanted pain without hatred and especially without fear.fear. And this acceptance also means a willingness to abandon some of our beliefs. To allow room for a faithful doubt, rather than a doubtful faith.

The moment we attempt to make our beliefs fact is the moment suffering begins. It can only give birth to anger, fear, panic and disillusionment and strengthen the fetters that bind us.

I don't think there's anything wrong with having beliefs, so long as we acknowledge them for what they are and are not. (Simply beliefs, not facts).

It is when the Ego attaches itself to our beliefs that we wade into trouble.

6

Comments

I spoke once with a lady who worked in palliative care. She said that she watched so many people at the end of their lives asking why God doesn't let them die because their pain had become intolerable. Believing that a God is somehow responsible for our pain - or on the other hand unresponsive to our need for relief from it - seems to be a belief that protracts suffering right to the bitter end. Belief is a funny thing, indeed.

At best, belief may function as provisional scaffolding which eventually leads to insight, which must be nourished and cultivated. But the scaffolding isn't what matters, but the building itself, in which the scaffolding plays a temporary role. But for many people of various religious faiths, they get stuck on the beliefs-- to them they aren't a means, but the end itself. And so faith is reduced to mere ideological assent. And the stronger this conviction, the more likely they are to want everyone else to nod their heads in agreement too.

'I am the door,' Jesus said-- but many won't walk through that door-- they stand just outside of the door praising the doorframe instead. 'The kingdom of God is within/among you' but they would rather find the kingdom in the church.

The Muslim mystic an-Niffari said in the Book of Standings, 'The letter does not enter presence. / The people of presence pass by the letter. / They do not stay.' --And yet many become fixated on the letter.

The Buddha said 'Therefore, Ananda, be a lamp unto yourself, be a refuge to yourself. Take yourself to no external refuge.' --but we are quick to cling to absolutes of right and wrong in a one-size-fits-all approach thinking enlightenment is a possession no different than a house or a car-- it is something 'out there' that you get.

'Truth' --whatever it is-- is not a verbal formula, it is something lived. We don't agree with 'the Truth,' rather we must learn to give birth to our own truth in the midst of our own unique and unrepeatable situation here and now. In a sense, that is what meditation is for, an open space within oneself to clear the mind of the clutter of beliefs and thoughts-- buried under all that clutter is the Buddha that we already are. It has always been under our noses, so to speak-- we only lack the developed skill and insight to REAL-ise it.

I think the intention was not to recognize whether someone was good or bad but to see what is beyond them. Living the middle way.

A friend is the one who beheads you.

A swindler puts a hat on your head.

A host who pampers you becomes your burden.

The Friend deprives you of yourself.

rumi

Sometimes Buddhists refuse the refuge of suffering.

Others run to it. Welcome to it.

I have little to say (besides "thanks"), really, except that I'm not convinced that suffering can always be dismissed as a choice, or "option." I think it may be more a matter of degree.

Of course, pain has a biological function to get us away from danger, etc.; but cannot suffering also have a function of alerting us that we need to get out of a ditch or onto a new path —off one we've been treading too long? I mean, etymologically "suffering" is "bearing" something (in this case pain), so suffering is not just a response, but an event in itself. Maybe it's dukkha (the suffering of suffering, the worrying about the morrow's sufferings...) that is the response. Suffering seems real to me; albeit dwelling on our pains doth seem to make it worse.

Also, I've long been "attached' to the notion that suffering has meaning (that is, a reason): which is to help us understand what other people are going through too and, thereby, to help build us into more compassionate beings. I know you touched on the subject of compassion in your paragraph following the Lin Yutang quote, but the "red herring" must have thrown me off.

Many thanks if you can set me straight on this.

The topic of “God and suffering” is not a new idea, and has been discussed throughout the centuries, and it all boils down to how one perceives and experiences “God”. If we project anthropomorphic sentiments upon the “the source of being beyond being” then we will invariable be perplexed by this question.

In the Genesis 3:17 story God tells Adam after tasting of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil that “cursed is the ground for thy sake; in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life”. From this it is quite clear that we are responsible for our own ignorance pertaining to duality, and the suffering that this orientation brings.

As children we believed in Santa Claus, but adults we must become Santa Claus.

(The example of childbirth makes for the better example of pain without suffering).