Best Of

Re: Meditating on ones emotional life

Looking outside to avoid what's inside, or looking inside to avoid what's outside, are both causes of our continued suffering. Additionally, inside and outside are really just the limitations of what we have decided is our boundary between self and other.

Mind and body (for me) work better as the states that result in suffering's cause when in disharmony and result in suffering's reduction when met with collegiality.

As a practice....

To the degree that we can meditatively allow, all phenomena their own unmolested interaction with all of our sense gates, turns out to be the same degree that life's unavoidable pains can be detached from sufferings causes.

how

how

Re: Quotes - discussion

All I know about is some of the reporting I've heard on the subject of science publishing.

There are several issues, the one that I remember now is that of the need to produce positive results. That a study that doesn't find what they were studying has a hard time getting published. Thus the researchers will play with the data to get positive results (I think this is called P hacking), basically they'll paint the target they're aiming for after they see where the data leads. The proposed solution would be to pre register experiments for what you're looking for and for journals to agree to publish regardless of the findings, as null results are just as important to the accumulation of knowledge as positive results.

person

person

Re: What is everyone's opinions on SAKYA BUDDHISM?

I’m assuming you mean the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism (Sakya). As Tibetan schools go it seems fairly heavy on the Tantric side, not really my cup of tea. But as a starter in Buddhism, any path is good, just stay sensitive to the feeling that this might not be right for you, and if that should come, maybe start exploring other paths.

Jeroen

Jeroen

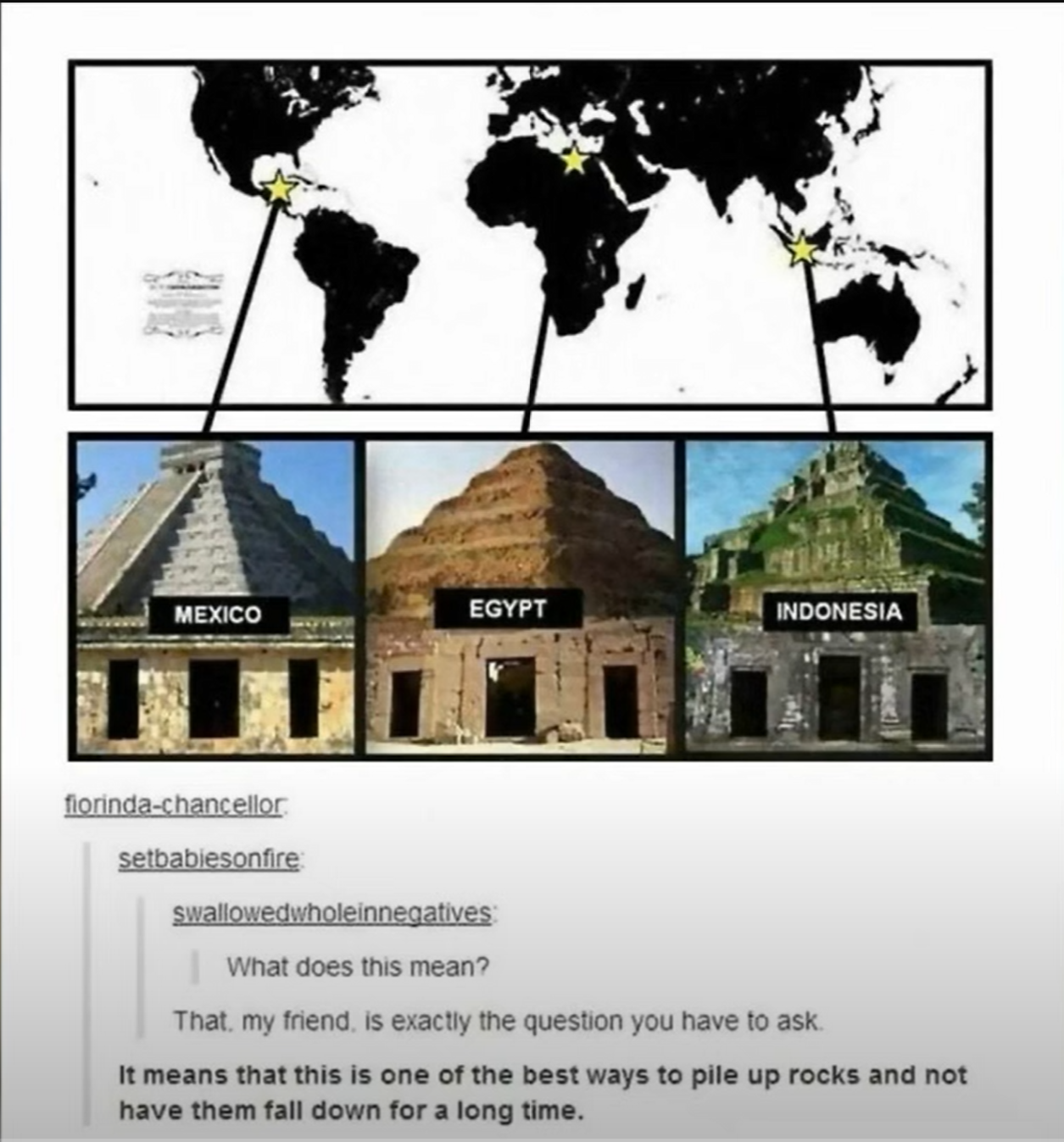

Re: Talking outside the echo chamber

Ed Barnhart speculated that the Macchu Picchu stones were shaped by acid. There are natural materials in the area that they would have used for other things that could be combined to make an acid powerful enough to weaken the stone and make them press together.

We've had plenty of examples of archeological things over the years that people had no idea how they were done only to have figured it out later. Its a sort of "Atlantis of the gaps" problem.

@Jeroen said:

The thing is, a lot of archaeology is educated guesswork based on the small evidence that is there. We try to construct pictures of the ancient world. Hancock is willing to go across the boundaries of fields into areas like the origins of terra preta, the Amazonian dark earths, or local legends on Malta about giants who build stone temples in a single night, to form a more complex picture of the past than just bone fragments and pottery shards. It’s interesting, is all I am saying.

If someone added historical stories of fairies, vampires and giants to the story of history they could make it more complex and interesting, but that wouldn't make it true. I think its a question of how we know what we know. Speculation is good, many currently accepted Theories about the world were considered crack pot at one point. But for every plate techtonics and germ theory there are many more hollow and flat earths, planet Vulcans, or wilder ideas.

Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method.[Note 1] Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims; reliance on confirmation bias rather than rigorous attempts at refutation; lack of openness to evaluation by other experts; absence of systematic practices when developing hypotheses; and continued adherence long after the pseudoscientific hypotheses have been experimentally discredited.[4] It is not the same as junk science.

person

person

Re: Quotes - discussion

I came across it in this interview, about 11:00 if you want the context:

Arguably since the last ten years or so, a new archetype has arisen — that of the Internet Influencer. This is about the predominance of marketing in the social marketplace over truth and science. This also shows up in the mess that peer-reviewed papers are in, with lots of make-work research and little of real significance showing up.

Jeroen

Jeroen

Re: Quotes - discussion

I like this.

Me too.

We hold on to many things:

- Life

- Body

- Past

- Emotions

- Self

Like onions, they make us cry.

Just like onion layers, they fall away.

No Onion.

Union.

lobster

lobster

Re: Talking outside the echo chamber

@Jeroen said:

Maybe not every idea Hancock comes up with will be true, but most of them are reasonably sensible.

Like, which ones?

There are things like mounds of Earth in a city like pattern in the US, it’s a question of just a few solid pieces of evidence being enough.

I suppose you're talking about Cahokia. There are more than a "few" solid pieces of evidence supporting, current thinking about it. There's a warehouse full of evidence in Milwaukee, from Melvin Fowler's excavations. I worked with several archaeologists who worked and studied under Fowler, and I met the man myself - he gave me a tour of that warehouse while I was visiting to check out possibilities for post-grad studies. But anyway, I digress ....

otherwise Hancock would be entirely unbelievable.

He is entirely unbelievable. He'll take something that's somewhat obscure to the public. He'll present a conclusion about it, then set up an argument to support it, which is ass-backwards science. People buy it, in large part because they don't know any better and have a high level of gullibility. He also shades modern history and archaeology, in order to erode confidence in them, and reinforce his own ideas. He's a kind of latter-day Erich von Däniken.

Re: Talking outside the echo chamber

@Jeroen said:

For example, in Macchu Picchu there are granite stone blocks of many tons and irregular shapes so precisely shaped and fitted to each other that you can’t slide a piece of paper between them. Granite is really hard stone, difficult to work even with the tools we have today.

That seems to assume that Incas were incapable of working with stone, as accurately as we see. It's quite obvious that they did, as there is no other plausible explanation. There are plenty of other example of the ancients' skill in working with stone. Ancient Egyptians, made huge granite obelisks to precise dimensions, using stone, copper and bronze tools. You can see the signs in the quarries they used near Aswan. Not only that, but they figured out how to get those obelisks down to the river, into a boat of sufficient displacement, and then travel downstream to what is now Luxor.

Granite isn't all that difficult to work with. Egyptians were able to carve Granite very precisely, as evidenced by their obelisks and statues. It's not as easy to work as limestone, but well within their collective skill set.

I've always thought that if advanced science was used, why didn't it include iron tools instead of the softer alloys they did use. Why no wheels, including pulleys, as well as block and tackle. Then there's their inability to render hands and feet on statues that were otherwise anatomically correct.

In the Museum of Cairo there is an oddly shaped artefact named the Sabu Disk, which is 5000 years old and made by an unknown technique. It too is made of stone, but it looks like a machine part.

I've seen it first-hand. It doesn't look like a machine part. It's made from schist, which has a similar mohs hardness as Marble. It could be easily worked with stone tools. What it was used for, I neither know nor care. If it was from a machine, it must not have been a very good one, as there is only one in existence and there are no records of its use.

What you site are not signs of advanced science. They're merely examples of culture we cannot explain at present.

Re: Important Stuff

Important Stuff

Meditation

Bodhidharma comes to mind...

""The most essential method which includes all other methods is to behold the Mind..The Mind is the root from which all things grow..If you can understand the Mind...Everything else is included""

Shoshin1

Shoshin1